Nowadays, you just can’t get through even one day without encountering plastic in some form. Grocery bags, coffee cups, even clothing – plastic is everywhere.

But it hasn’t always been this way.

In fact, plastic wasn’t invented until the last century – as in 1907 Leo Baekeland will go down in history as the inventor of Bakelite, the first fully synthetic plastic containing no molecules found in nature.

It was also the day humanity began its love affair with one of the world’s most pervasive pollutants.

Australians are now using over 3.5 million tonnes of plastics each year, according to WWF, with one million tonnes made up of single-use plastic.

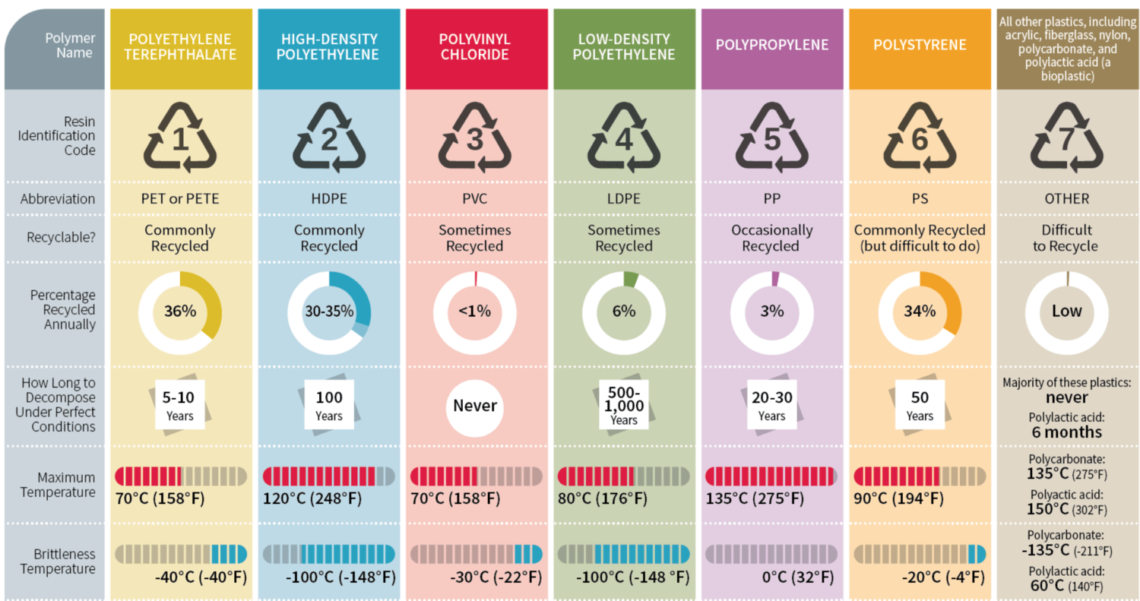

Today, there are seven most common types of plastic, and each take a different amount of time to break down. For example, a styrofoam cup and a plastic bag may never break down, only break up into smaller pieces called microplastics.

It is unknown how many centuries it takes for plastics to completely break down and “disappear”.

Microplastics are now found everywhere scientists have looked for it: deep in oceans, in the food we eat and the salt we season our food with. In 2015, oceanographers estimated there were up to 51 trillion particles of microplastic floating in surface waters worldwide.

We might be ingesting around a credit card’s amount of microplastic every year.

The 7 types of plastic and how long they take to degrade. Image: Plastic Busters

So now that more people across the globe have started to wake up to the tide of plastic swamping our planet, it seems that the people have spoken.

A new survey by research company Ipsos has found that more than three quarters of Australians want single use plastics banned.

Among the findings:

- Three-quarters (77 per cent) of Australians and a similar number of people across 28 countries agree that single-use plastic should be banned as soon as possible

- 86 per cent of Australians, and on average 88 per cent of people globally, believe it is essential, very important or fairly important to have an international treaty to combat plastic pollution

- 82 per cent agree that they want to buy products that use as little plastic packaging as possible (in line with the global average)

- 86 per cent agree that manufacturers and retailers should be responsible for reducing, reusing, and recycling plastic packaging (slightly higher than the global average of 85 per cent).

The Global Advisor survey was conducted between 20 August and 3 September, with 20,513 adults from 28 countries responding.

“These results make it very clear that there is a strong consensus globally that single-use plastics should be taken out of circulation as quickly as possible,” said Ipsos Australia director Stuart Clark.

“People want to do the right thing. An average of 82 percent of people surveyed want to buy products that minimise plastic packaging. They want that change to happen quickly and they want their governments to support it.”

The Ipsos study will be featured by Plastic Free July and WWF leading up to the upcoming UN Environmental Assembly (UNEA) 5.2.

According to the study, the five countries with the highest levels of agreement in favour of banning plastics are Mexico (96 per cent), Brazil (95 per cent), Colombia (94 per cent), and Chile and Peru (both 92 per cent). Those with the lowest ones are Japan (70 per cent), the US (78 per cent) and Canada (79 per cent).

According to a comprehensive report from the Plastic Waste Makers index, 20 companies are responsible for producing 55 per cent of all the single-use plastic waste in the world.

ExxonMobil has been named as the greatest single-use plastic waste polluter in the world, contributing a whopping 5.9 million tonnes to global plastic waste. The largest chemicals company in the world, Dow, created 5.5 million tonnes of plastic waste, while China’s oil and gas enterprise, Sinopec, created 5.3 million tonnes.

Eleven of the companies are based in Asia, four in Europe, three in North America, one in Latin America, and one in the Middle East. Their plastic production is funded by leading banks, chief among which are Barclays, HSBC, Bank of America, Citigroup and JPMorgan Chase.

“An environmental catastrophe beckons: much of the resulting single-use plastic waste will end up as pollution in developing countries with poor waste management systems,” the authors of the report said.

“The projected rate of growth in the supply of these virgin polymers … will likely keep new, circular models of production and reuse ‘out of the money’ without regulatory stimulus.”

More than 190 governments will meet in Kenya from 28 February to 2 March 2022, for the UN Environment Assembly (UNEA) to consider negotiating a treaty on plastic pollution.

But some companies are leading the way to reduce their plastic waste.

One company that is leading the way in banning plastic is ALDI Australia. The supermarket chain removed almost 2000 tonnes of plastic packaging from its shelves – that is a reduction of 10 per cent in the past year.

The company has more than halved its use of difficult to recycle black packaging, such as meat trays. It claims that 84 per cent of all packaging is now recyclable, reusable or compostable, and 65 per cent of the ALDI range now carries the Australasian Recycling Label (ARL).

ALDI’s target is to reduce plastic packaging by 25 per cent and have all packaging be 100 per cent recyclable by 2025, in step with the 2025 National Packaging Targets.

ALDI announced in December it will become the first major Australian supermarket to introduce paper straws on its beverage cartons, most notably the “humble and nostalgic” juice box, or ‘popper’.

“Australian grocery buyers are informed and want to be able to make conscious purchasing decisions,” said ALDI director of corporate responsibility Daniel Baker.

“The next few years will see us continue to remove plastics from our range and by 2025 all remaining packaging will be either recyclable, reusable or compostable.”

The grocery retailer says it has already removed a number of unnecessary and problematic plastics from its range, last year swapping out single-use plastic tableware, saving 322 tonnes of plastic from landfill, as well as replacing plastic cotton buds with a paper-stemmed version, avoiding over 357 million plastic stems from ending up in landfill each year.

Another company that has vowed to phase out plastic in consumer packaging is IKEA. The homewares retailer has already significantly decreased the use of plastics in their packaging, with the company claiming that less than 10 per cent of its total volume of packaging consists of plastics, with a plan to phase out plastics altogether in stages.

In some countries and states, plastics are already banned.

Around the country

In the Plastics Circular Economy Act 2021 legislation NSW banned single-use plastic bags, straws, cutlery and other items, to be phased out by November 2022. And in the ACT all public events will be plastic-free from July 2022 when the second phase of the Plastic Reduction Act comes into effect.

South Australia’s ban on single-use plastics (plastic straws, drink stirrers and cutlery) started on 1 March last year. The Queensland government’s Plastic Pollution Reduction Plan proposed to ban plastic straws, stirrers, plates and cutlery from 1 July 2020.

Worldwide

France has banned plastic wrapped fruit and vegetables including carrots, apples and bananas (the fruit that already comes wrapped!), estimating the ban will remove 1 billion pieces of single-use plastic packaging from circulation per year. The country plans to phase out all single-use plastics by 2040.

More than 80 countries now have a full or partial ban on single-use plastic bags, including more than 30 African countries, according to non-profit Planet Patrol.

Meanwhile researchers are working around the clock to develop innovative plastic replacements.